It is incredibly rare “for any designer to spend this much time in rehearsal with actors.” (Collins, 2011, 23) Given that in this module I chose to make sure I was at every rehearsal, regardless of whether I was called in or not, I was able to get a real feel for what the performance called for, and I was able to bring sound in from an early stage. In a production of Titus Andronicus, sound designer Collins took a similar approach. In his writing he talks of being able to understand the performance the entire way through the process, much like I did, and he talks about an “opportunity in this to perform – albeit from just off-stage… I had found that I could make my relatively crude playback devices work in perfect sync with their performances.” (Collins, 2011, 23) This was something I found I was able to do too, and was able to match sounds to the performances that took place, like making sound change slightly when people entered or left the room.

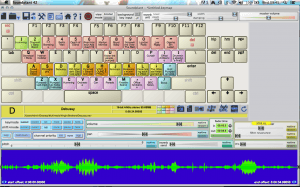

I chose to use a program called ‘Sound plant’ which we explored use with earlier in the module. The program allowed me to load sounds in, and play them along with a click of a button of my keyboard. I was able to loop, overlay and match the sounds to the exact second that needed to occur. This was helpful in every rehearsal and the plan is to use it in the performance live too with the audience being able to see what I’m doing at all times on a TV screen connected to my laptop.

A screenshot of soundplant, with my sounds loaded in.

I started to refer to myself as a historical DJ. Taking moments of history or using other sounds to reconstruct or add to moments from time. “The DJ activates the history of music by copying and pasting together loops of sound, placing recorded products in relation with each other.” (Bourriaud, 2002, 18) Whether or not it actual music or sound effects, I managed to play sound files and edit them live, along with layering to create the exact sound that needed to happen. I was able to fade in and fade out tracks live along with the action, add reverb or low pass filter when needed and overall create a live and interactive feeling to the sound.

For some time, I was also to play piano for one scene too. Yet this was decided against to strip the scene back to its core. The piano playing distracted and it was better for me to focus on using soundplant. However the Hitler scene, once made, required some kind of ‘substance’ behind it. When looking at a lot of the speeches he made online, a lot had that kind of old time recording noise just underneath them. I wanted to replicate this, but every sound file I could find didn’t sound real enough. Luckily I owned a Vinyl player, so I chose to have that live, I just let it loop on the end of the vinyl so what was played was the crackling noise of a vinyl player. This led me to be able to create a sound in an unorthodox manor, and by having a camera on the player for the audience to see, they are also able to tell what is going on.

Overall sound is incredibly important for making a show meatier and more emotional, and I feel by using the programs and live creations I did, I was able to give a more enjoyable and entertaining element to what would have otherwise just been queued up in Cue-Lab.

Works Cited

Collins, J. (2011) Performing Sound/Sounding Space. In: Kendrick, L. and Roesner, D. (eds.) Theatre noise: the sound of performance. London: Newcastle Cambridge Scholars.

Bourriaud, N. (2002) Postproduction. New York: Lukas & Sternberg.