The ethos of both the process and the performance as a whole identifies itself within the collaborative efforts of each performer, encapsulating individual theatrically artistic images personal to the individual. Each of these personal ideologies constructed themselves alongside a vast collaborative cascade of inspirational theories, personal interpretations and explorations, influential images, times, and prior impacts.

Reflecting on my understanding of the transformation of the process I’ve noticed particular areas where significant decisions and explorations made the most impact on the construction of the final performance. Looking through the notes on the process I made after and during each rehearsal here is a comprehensive timeline of the journey the group took in developing Changing Faces:

My initial contribution to the process, with regards to developing an initial piece lay in two areas of exploration that fell beneath one main area of study/inspiration; psychology. The first idea proposed was based on the Charlotte Perkins Gilman novel The Yellow Wallpaper which explores the madness of solitude and the development of a troubled mind, alongside, attitudes towards feminism, and the female identity in past examples of literature. The choice to propose this text was specifically inspired by my interest in the human psyche. Whilst performance itself may explore the mysteries of the human mind and open up performative examples of emotion, my interest was to see how the action within an enclosed space is read through camera and projection. The staging concept at this point was large perspex boxes that were wallpapered from the inside, in an open space, with cameras pointing into one corner of each box giving the illusion of fly-on-the-wall, as the performance progressed the wallpaper is stripped away to reveal the live body. Following along this same interest of human psychiatry, I also suggested exploring understanding human identity and how a loss of personal identity causes shifts the psychology of the individual. Using psychologist, Philip Zimbardo’s The Lucifer Effect, the aim would be to explore the human capacity for evil once the personal identity is either deconstructed or obliterated totally. The staging concept for this idea used a large perspex sheet separating the spectator from performer, and using ‘Makey Makey’ spectators can activate sound clips and camera projection to choose their own viewing point via the eye of the lens situated within the playing space.

From this inspiration we began to consider the deconstruction of significant factors that form human identity, and how we interpret them. This led us down two pathways, the first being considering in what way identity can be deconstructed, and considering the potential impact technology may show. This was inspired by the notion of the online ‘world’, migrating into real life, an example of this is RPG, “…the boundaries between game worlds and “real life” became increasingly tenuous.”(Filewod, 2014). This was a defining moment within the process as it began to inspire new thinking into how easy or indeed, difficult, the presence of technology has made our ability to know one another. How real are the people online? Are they a heightened projection of our inner psyche, programmed to operate within the virtual space? These questions led to our second pathway of exploration, the concept of anonymity in virtual space, using the blog site ‘Tumblr’ and avid user Claudia Cross, we encouraged unknown users to send in the dark thoughts and processes their mind had adopted under an anonymous post. The main concept produced from this pathway was specifically the identification and isolation of interpreting identity, and the ease of access media allows us to know a person without having to even meet them, and how we could view the individual – the online personality vs. the live person through the eye of a camera lens; CCTV.

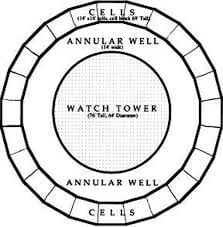

From this notion of CCTV we considered surveillance and the impact of its presence and also, the conspiracies that surround its function, i.e. ‘Big Brother State’. By this point in the process it was evident that the group required the consistency of one notion and so, the G.O.D. was born. Presented as a fresh concept during small group based tasks I assigned Jack and Cherry’s group kickstarted the idea of a controlling faction and conspiratorial government operating within a dystopian future projecting the ‘control’ of two contemporary structures, Government and Religion. This was the first moment during the process that the group managed to achieve their most completion of tasks myself and Bryony began to set. The rehearsal time and space became our sacred playground to explore each new idea individuals were producing, becoming a real life forum of play. Whilst, the tasks were completed away from the space, performers went away with set instructions and questions such as writing tasks, (Imagine this is your final message, what do you say? What rules would you make in a dystopian future?), that they had to follow and answer, and return with their work. However, during this process it began to become clear that what was being developed followed our preconceived notions of performance, the G.O.D. dynamic has shifted from our goal of multimedia and instead, became a play. Once Bryony and I began to notice this, we encouraged the group to begin furthering the exploration of prior ideas. The issue with the G.O.D. concept lay at the foundation which was that, we sought to establish a dystopian, totalitarian, autocratic environment neglecting to notice that such states already exist (North Korea). Now we had a hurdle to cross – how could we transform the temporal, and how do we show the transformation of current culture to this dramatised new culture? We immediately noticed the first issue we hoped never to experience, the large group, had large ideas, and the net of inspiration was spreading rapidly. We were using such materials as Orson Wells’ 1984, my inspiration from graffiti artist Banksy’s work, personal opinions on the decline and rise of religion, and Michel Foucault’s philosophy of the Panopticon amongst many others. So we chose to revert to our prior exploration.

With the concerns of temporal performance dynamic fixed within our heads we revisited dark thoughts and identity and explored the performative nature of the verbatim posts provided through tumblr and its relation to the camera. It became clear at this point that the performance needed a firm inspiration, a fixed one-liner that could be easily adapted, interpreted, and understood. Thankfully, Adam had been posting regular materials for new consideration consistently throughout the process that gave us an insight into his operations in the role of writer. This was presented perfectly, when Adam suggested the use of William S. Burroughs’ quote, “When you cut into the present the future leaks out.” (Gallagher, 2013). This quote was taken from Burroughs’ comments regarding Brion Gysin’s ‘Cut-Up Method’ and would be the platform for the new concept of playing with the temporality of the performance. Now that we had reaffirmed the difference between play and performance, we used Burroughs quotes to negotiate themed responses, and the task for everyone was simple, consider the quote and produce an image in response. Unfortunately, no-one in the group actually achieved this, and the unfortunate realisation that we were at this point within the Easter holidays made it extremely difficult to enforce the expectations we demanded as directors. Instead, in the second week of holidays a small amount of the group met up with Bryony and Jack was given control of the session to discuss his new concept that would later be the basis for the final performance. What Jack seemed to have done was to revert the given instruction of a responsive image or vignette that considered the present impacts on the future, instead, looking to the past and the impacts specific moments in history had upon the present. The idea explored the assumption that we would produce a new perspective using the camera, to show an alternative view of what we already knew from pre-existing mediated imagery (e.g. Marilyn Monroe singing ‘Happy Birthday’ to President Kennedy, 1962).

Following Jack’s concept the group explored moments in history they believed to have an impact on the world today or changed our understanding of humanity and our environment. As ideas began to solidify and members of the group began to take ownership of scenes it was decided that culminating elements of prior exploration and amalgamating certain assumptions to meet the criteria of the new pathway. We considered the relation between the mediatised image and the live action on stage, reflecting again on concerns surrounding the nature of surveillance and the impact the lens of the camera made on our individual interpretation of imagery and action. I suggested to that the group consider an almost rotational dynamic, in which each constructed mediated image (i.e. projection), would have its meaning altered with the transformation of the live body’s presence/action/appearance. However, this was ignored and it appeared that the whole group did not ‘buy into’ the idea, and instead focused on in which was to explore the alternative perspective of each historical moment. The only way that this idea of the rotational platform was somewhat reflected was within the staging design that was inspired by the panopticon. By providing a raised structure in the background (the central tower) the playing space became the window of action (individual cells), with the cameras moving within each moment. Once Bryony and I had identified the direction the process was moving, and after we began allowing more freedom within the group, two significant decisions were made: First, no performer will assume to ‘be’ their character, only to represent the figure in its moment. Second, the construction of the image would be visible, the spectator will see everything.

The reason for these two rules followed the group belief that we could expose the assumptions of the media when it considers significant moments in history. What we failed to notice through this decision, was the contradiction we were making. We had created a multimedia performance that dramatised assumptions representative of moments within history using technology, in an attempt to expose the construction of mediated imagery.

Reflecting on the role of Director, I can identify that my personal approach to both the process and the overall artistic image was extremely collaborative with Bryony, and in many ways both aspects of my directorial style were both aided and hindered due to this decision. Throughout the process, our personal styles of approach in terms of director ‘types’ fluctuated between the confrontationalist and creative artist. When one of us was actively influencing the structure of the piece, invading the space of the performer, the other remained ‘behind the desk’ to oversee each scene against the backdrop of the overall aim. This often led to negotiating and highlighting the impact to the aesthetic each decision produced. This was certainly the case when I found myself operating within the space alongside Adam Ragg, constructing the performer intentions during the ‘Assassination’ scene, giving specific direction to form the relationship between the performer and the camera. I attempted to draft out a pattern of movement for Adam that negotiated with the figures on stage alongside his monologue, as well as altering his approach to be consistent with our chosen movement style throughout. Bryony could aid the process by noting the interference Adam’s position made with the camera and therefore the projected image, due to her position in the rehearsal room, observing from the spectator point of view. There is an uncomfortable truth that whilst collaboration can produce spectacular work, (as evidenced by this performance), the ability to truly explore a personal artistic image is consistently threatened by you co-director and your cast. However, it is important to note that multimedia performance was a brand new concept for me to understand and in many ways I was in a new arena that I assumed to grasp prematurely based on my assumption that my directing style, adopted during the Directing module, would be suitable for this work. Directing a pre-existing play is incredibly different from the directing style required for this module, and although my exploration of personal inspiration formulated my artistic image, communicating my ideas was not always the most productive, and often when I did provide stimulus, it was overlooked or fell on deaf ears, due to the decision to work collaboratively. The resolution for this was to continuously ensure that final decisions were left in the hands of myself and/or Bryony, so that we could be confident that an artistic image was not entirely obliterated by the sheer volume of creativity provided by the group.

This decision to ensure that final decisions were ours alone was evidenced by our ability to received feedback and elect to either adopt the ignore the suggestions provided. Often I agreed with the feedback, such as the suggestions to strip each scene to its minimum, this made every scene more powerful in its simplicity, and did not over complicate the space. Another example was the decision to bring Connor and Jake out of the wings, and instead place them firmly in the space; this decision highlighted how Connor’s relationship towards the space was underestimated. The body, whilst live, existed outside of the spectator’s preconceived interrelation of the spatial. The mediatised image presented to the spectator’s interpretation initially intended to play with the concept of live body necessity, based on Phillip Auslander’s statement that, “The ubiquity of reproductions of performances of all kinds in our culture has led to the depreciation of the live presence” (Auslander, 2000). And yet, the mediatised image is limited in the sense that it is a fixed structure, with a fixed window of ‘sight’, and the ontological relationship of the camera and the body in its space was compromised by the spatial environment. Therefore, presenting the body of the performer in the onstage, dissolved the necessity for a new environment, it instead the live, immersed itself into the space, and the spectator now viewed the relationship between the body and the camera, freeing movement, and performability. Connor was no longer performing to an empty space or relying on his personal vision, instead he was performing to the camera, and therefore, to the spectator. The aesthetic was no longer undermined but the spatial stretch was altered, it was no longer physical, but truly mediatised – movement and performance existed in a transfer between body-to-camera-to-projection-to-spectator.

When considering the final performance of Changing Faces it is difficult to express its reception. What I noticed from the performance was certainly areas that left much to be desired, specifically in regards to the utilisation of the technology. Visually, the camera work followed the direction Bryony and I gave, the position of the camera was suitable and correct for the majority of the performance. However, I believe that where some angles and close-ups reflected our desire to alter the perspective of the spectator, opportunities were missed. An example of this was evident in the ‘Coronation’ scene, where the image being projected appeared to have very little instinct to select a point of focus, and lacked faith to maintain focus for a longer period of time. If the camera had focus on the movement and positioning of the hands, I believe it would have communicated our desire better. Nevertheless, the camera communicated what we intended, and from a spectator perspective, I was given the opportunity to view the individual in an alternate space than what the live body allowed. Regardless of the constant technical failures, I believe it is imperative to note that the presence of the cameras, (when projecting), achieved to communicate and play with spectator perspective. My main issue with the performance was the transitions and construction of each scene. Whilst still an interesting activity to observe in the live, the transitions lacked the direction given and unfortunately gave off a clumsiness. Given the opportunity, I would have selected ‘pathways of action’ mapped out on the stage space by colour coded tape individual to each performer. This would mean that the performer could not deviate from their given pathway, and would have provided a fluidity that the live performance lacked. However, my understanding of the performance was confirmed by the finish piece, and as I watched the final performance, I witnessed the culmination of each influence and impact every member of the group provided and recognised that the direction given whilst not always adhered to, was a material that worked alongside others to produce and shape a significant example of performance and the relationship it has to media.

Cite List

Anonymous (2015). Dark Confessions. [online] Available from http://dark-confessions.tumblr.com/

Auslander, P (2000) Liveness, Mediatization, and Intermedial Performance. [online] Lincoln:Blackboard. Available from https://blackboard.lincoln.ac.uk/bbcswebdav/pid-940041-dt-content-rid-1799097_2/courses/DRA3044M-1415/Auslander%20-%20Liveness%20and%20Intermediality.pdf

Banksy. (2006) Banksy Wall and Piece. London: Century.

Climenhaga, R. (2009) Pina Bausch. Oxon: Routledge.

Filewod, A. (2014) Patch Notes: Playing the Selves in Gamespace. [online] Lincoln:Blackboard. Available from https://blackboard.lincoln.ac.uk/bbcswebdav/pid-940046-dt-content-rid-1799101_2/courses/DRA3044M-1415/Playing%20the%20Self-Gamespace.pdf

Gilman, C. (2012) The Yellow Wallpaper. [online] Available from https://www.gutenberg.org/files/1952/1952-h/1952-h.htm

Hansen, L. (2013) Making do and making new: Performative moves into interaction design. [online] Lincoln:Blackboard. Available from https://blackboard.lincoln.ac.uk/bbcswebdav/pid-940042-dt-content-rid-1799098_2/courses/DRA3044M-1415/Making%20Do%20and%20Making%20New.pdf

Jacobs, B. (2012) Kennedy Rice Speech. [online video] Available from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FYb_mhiE-qU&feature=youtu.be

Laermans, R. (2012) ‘Being in Common’: Theorizing artistic collaboration. [online] Lincoln:EBSCOhost. Available from http://web.b.ebscohost.com.proxy.library.lincoln.ac.uk/ehost/pdfviewer/pdfviewer?vid=2&sid=6ee35003-e94b-45a2-bf79-5dd9f241689f%40sessionmgr115&hid=115

Ruggill, J. and McAllister, K. (2006) The Wicked Problem of Collaboration. [online] Queensland:M/C Journal. Available from http://journal.media-culture.org.au/0605/07-ruggillmcallister.php

Tullin, J. (2015) Changing Faces Brand New Trailer! [online video] Available from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Fo-5Cb5gwoE&feature=youtu.be

Zimbardo, P. (2007)The Lucifer Effect: How Good People Turn Evil. Reading: Rider.