Start-up Menu

“growing up in a culture where most of us spend our time in front of screens…it is the most natural form of vocabulary to use”

(Tecklenburg, 2012, 12)

Going in to this module I knew very little about technology and multimedia in performance, so I was eager to learn about the various equipment and performance techniques that have “challenged the very conception of theatre” (Bay-Cheng et al, 2010, 13). Following some intriguing research into temporality and the virtual world, I quickly discovered that ‘multimedia’ was in fact a blanket term for many various technical collaborative styles and in fact I was already aware of some of the techniques from my own previous experience in stage and television performance. Rather than a separation from live theatre, multimedial performance concerns itself with “merging the conventions of performance, film production, and film viewing” (Tecklenburg, 2012, 22) into a single space, combining the live body and the mediated technology. This creates the potential for such performances as Revolution Now! (by Gob Squad), Virtuoso (by Proto-Type Theater) and Jet Lag (by The Builders Association), each performances with a unique take on the technology induced stage.

It was decided that we would remain as one large group and so divided ourselves into performers, directors, technical teams and all manner of theatrical designers. Taking inspiration from these performances, our group set to work conducting our own experiments with the vast range of technology available to us, including cameras, projections, soundplant, vision mixers, smoke machines and many other technical paraphernalia.

Jet Lag Performance Clip (The Builders Association, 2009)

Testing, testing.

Though slow to start, our creative process went through many ideas in the beginning, sparking a great deal of practical and written experimentation as a means of developing potential characters and plot. Though not all of these activities came to a fruitful end, the initial test period did prove useful for ruling out some ideas and giving us a clearer idea of the direction we wanted our piece to take.

One of these tests was centered around the notion of surveillance andthe intrusive technology in every day life. Members of the cast were instructed to record themselves or housemates performing a seemingly mundane activity whilst being unaware of their being filmed. The idea was to observe the effects of people in every day life and consider the ways in which the unknown presence of a camera affected ones “performance of self” (Bay-Cheng, 2010, 80).

Interestingly, those that recorded themselves, myself included, noted that although they were attempting to act natural, each felt very conscious of the lens and in some way over-exaggerated their activity, whereas those that recorded others noticed no change in their personal behavioural habits for as long as they remained unaware of the observational presence. Tecklenburg observes this same behaviour and theorises that the mechanical eye offers the public “a strange authority” (Tecklenburg, 2012, 26) and the liberty to behave in a performative or calculated manner dissimilar to their usual idiosyncratic behaviour. This experiment and the resulting theory of performance liberty would later inspire one of our more favoured performance ideas.

God is Watching

“The eyes of the LORD are in every place” (Proverbs 15:3, King James Bible Online, 2015)

In the 21st century, we find ourselves very much dependant on technology; for entertainment, for support in our daily lives and for our supposed protection. Technology in many forms watches over our daily lives with a zoomed lens, but what happens when the camera sees too much?

Taking inspiration from George Orwell’s 1984, one of our primary ideas was to construct a staged Big Brother state and imply a potential future wherein a community, in this case our audience and cast, lived under constant surveillance and the fear of an invisible higher power. It was our hope that this concept would highlight the intrusive possibilities of technology and make audience’s contemplate whether or not this advancement marks the “end to privacy” (Reid, 2013, 10) or a sacrifice of privacy for the “common good” (Reid,2013, 8).

This process began with the creation and selection of supposedly extreme rules we might impose upon our captive community including restricted nutritional intake, uniform clothing, forbidden language, the implication of extreme punishment, and of course an ever watching symbol of power; the lens of our camera. What intrigued me most about this idea were the similarities between the rules we had fabricated and the reality of certain pre-existing communities. Given my own religious upbringing, I used the examples of the Mormon faith and compared some of its rules and restrictions to the ones we had created: restricted diet, monitored clothing, forbidden language, and of course the ever watching presence, God. Needless to say I was fascinated by the links between modern religion and our fictional totalitarian state and the resulting research inspired the creation of our own Big Brother whom we titled the Government of Development, or G.O.D.

Unfortunately this concept eventually led to a number of complications and an eventual dead end, but the connections and research we conducted led us to other passages of thought and that would eventually inspire and develop into our final piece.

G.O.D poster (Tullin, 2015)

The Camera Always Lies

From home recordings to worldwide news, while there remains a body behind the lens, the camera will always offer a selected vision of the bigger picture, a bias suggestion of events. It is under this assumption that we began our final production process; looking at famous and mediated moments of history from a different point of view and asking this simple question: ‘what didn’t the camera see?’

This all began at the suggestion of our classmate and technical team member, Jack Tullin, who offered the recording of Marilyn Monroe singing Happy Birthday to president John F. Kennedy as an example. He explained that while she was famously late to appear at the event, there was no confirmation as to why. This sparked great speculation among our group as to what might have happened and opened the door to consider other moments in mediated history that we could subvert and consider from different angles. This begs the question, what moments in in history should we represent? What are the most important moments? Arguably there are too many to count, but our final selection of events was chosen based on cultural significance, mediated popularity and personal preference. Each ‘moment’ would be its own scene in a fragmented whole displaying our own biased opinion of these unknown events. These moments were:

- The Moon Landing

- Watergate

- The Wright Bros.

- Emily Davison and the Suffragettes

- The Big Bang

- Queen Elizabeth II’s coronation

- The Columbine School Shooting

- The Assassination of JFK

- Churchill

- Hitler and Anne Frank

- Freddie Mercury and AIDS

- Newsroom

Each scene was given to one or two members of the group to conduct their own research and ideas which would later be edited by the rest of the group with the central focus of ‘the other point of view’ which gave some interesting results. For example, upon researching John F. Kennedy’s assassination, we thought it best to focus on his killer, his thoughts and reasons for killing the president. In the case of Queen Elizabeth II’s coronation, we all but ignored her crowning and concentrated on Elizabeth as a vulnerable twenty three year old woman. By publicising these potential moments, we moulded our performance with the idea of showing people that what we see with technology is not always the truth, further supporting our illusion by finishing the performance in a newsroom and highlighting the misconception of modern media today.

This act of illusionary representation was not only achieved through deisgn of concept, but in the delivery of the actors. Early into the process it was agreed that actors should make no attempts to ‘be’ their characters for this may deter from our main focus. This is not a performance to show actual events of actual people, it is entirely speculation and largely fabricated, therefore the actors need not look or sound like their counterparts in order to draw focus to the event and scene as a whole rather than the individual.

Watergate (Feedback Theatre Company, 2015)

Wright Borthers (Feedback Theatre Company, 2015)

Ready, Set, Go!

“design is not an end in itself but a way of making one more aware”

(Thorne, 1999, 25)

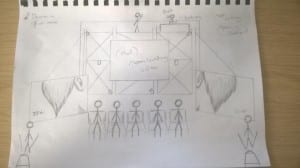

One of the toughest challenges of this process was our complete lack of suitable rehearsal space for a performance of this scale. Though our final piece would take place on the LPAC stage, finding the room to rehearse such a large performance in the business and law building was a herculean task, one not aided by our inability to access the equipment we required for our technical explorations. Thus I took it upon myself to create a series of set designs in order to aid our temporary creative blindness.

We went through several designs before finally settling on a broad stage with platform scaffolding and three large screens, creating a technically detailed but performatively spacious area for our actors to roam.

Set design for Moon Landing (Povall, 2015)

Set design for Assassination (Povall, 2015)

The Final Set, Platforms (Feedback Theatre Company, 2015)

Traditionally “design reveals a state that is unique to people, place and time” (Thorne, 1999, 25), so it was difficult to consider how we might create a single set for all variations of time and place, from The Big Bang to a BBC newsroom. Instead we decided to focus on the literal creation of each scene in order to support our satirical contemplation of what may have happened behind these famous events. Consequently, the metallic and tech heavy set worked in favour of this creation method, mimicking technical feel of a studio or film set rather than a naturalistic stage setting. This intention was further supported by our very visible technical team, four of whom were supporting the cameras on stage while a further two were situated atop the platform throughout the performance, controlling all visual and audio cues live from their desk.

Overall I feel that the intention of creation and manipulation rather than factual representation was well exhibited in this set design and accurately demonstrated that “the essential element does not reside in the result, in the finished work, but in the process, and in the effect produced” (Radosavljevic, 2013, 36).

Changing Faces – Tech Day

As I’ve often found with tech days, the setup and runs before our performance day were relatively stressful and full of necessary last minute changes, from a rearrangement of the lighting to the setup of each live feed camera onto the correct projection screen. Perhaps the most difficult part of the day was our first attempt to run our show with complete audio and visual cues. This proved to be a somewhat scattered and disorganised affair as a result of it being the first time we had had a chance to use our full setup since the beginning of these proceedings and as such caused a great deal of tension and discord within the group. From an acting point of view, I found the most problematic areas to be the transitions between scenes, particularly the movement of cameras and the impending risk of wires within the space as others attempted to shift chairs and tables in a performative manner. In order to resolve this as quickly as possible, we spent a great deal of time running over these moments in the limited time we had left, and although there was still some concern for how things would play out the next day, we did achieve a much more structured from of transition, taking meticulous care as to who would move each chair or how the assigned cameramen would manoeuvre the wires away from moving cast members.

Having been assigned to the team of four cameramen, my main concern was how to handle the cameras with accuracy and delicacy during the performance and, as an extra precaution, we were each given a brief re-instruction on how to use the cameras and handle them to the best of our ability. Given our lack of practise with these technical instruments, I greatly appreciated this short instruction and spent some time engraining the correct hold and movement into my mind before the show, a practise that proved very useful in the final performance.

Pull the blackout Curtains Down – Performance Review

The final performance came with a great many problems, largely ones that I am pleased to say we were able to recover from with little consequence to the overall performance itself. Each cast and crew member, and in particular our stage manager Charlotte, was able to quickly resolve situations of faulty tech, misplaced props and hasty costume changes to ensure the audience’s experience suffered little hindrance. From the wings of the performance, the process seemed to run smoothly and I believe this a testament to our groups calm demeanor and professionalism during this performance.

Unfortunately, many audience members marked that although the work was entertaining and interesting to watch, they were confused by the through plot of the performance and questioned our reasoning for putting on such a show. In hindsight, it is possible that we, being so involved in the creative process, neglected to fully transalte our idea from the paper to the stage. Regrettably, we may have been so drawn to the idea of “fetishiz[ing] the technology” (Dixon, 2007, 5) that we lost sight of our artistic vision in the process. Perhaps if we had taken more time to consider our work from an outsider’s point of view, we might have thought to include a through line plot device such as a form of text or linking imagery throughout these fragmented scenes.

Though long and difficult at times, this process has certainly been an educational one and I believe that our group has created an intriguing and imaginative performance, one that was performed to the best of our ability.

Changing Faces Poster (2015)

Works Cited

Bay-Cheng, S., Kattenbelt, C., Lavendar, A., Nelson, R. (2010) Mapping Intermediality in Performance. Amsterdam, Amsterdam University Press.

Dixon, S. (2007) Digital Performance: A History of New Media in Theater, Dance, Performance Art, and Installation. London, The MIT Press.

Feedback Theatre Company (2015) Media Gallery. Lincoln.

Povall, C. (2015) Set Designs. Lincoln.

Proverbs 15:3 (2015) King James Bible online. [online] place and publisher unknown. Available from www.kingjamesbibleonline.org [Accessed 23 May 2015].

Radosavljevic, D. (2013) Theatre-Making: Interplay Between Text and Performance in the 21st Century. Basingstoke, Palgrave Macmillan.

Reid, M. (2013) United States V. Jones: Big Brother and the “Common Good” Versus the Fourth Amendment and Your right to Privacy. Tennessee journal of Law & Policy, 9 (1) 7-43.

Tecklenburg, N. (2012) Reality Enchanted, Contact Mediated: A Story of Gob Squad. TDR: The Drama Review, 56(2) 8-33.

The Builders Association (2009) Jet Lag. [online video] Available from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5nPi-DDqa0Q [Accessed 24 May 2015].

Thorne, G. (1999) Stage Design a Practical Guide. Marlborough, The Crowood Press Ltd.

Tullin, J. (2015) G.O.D Poster. Lincoln.