What even is a Technologist?

When our ensemble first set out to create our Multimedia performance, I knew I wanted to explore a different aspect of production, technology. I’ve always considered myself fairly ‘tech savvy’, and have had some experience with the operations and process of Media production at A Level, but I’ve never had the opportunity to really challenge myself and contribute technologically to a grand scale performance. So when the opportunity presented itself within this module, it was impossible to not jump at the challenge. The process has been difficult and trying, but I’ve learnt a lot over the module and the culmination of the final show was to me spectacular, but early portions of the production process was often stilted.

With various ideas of the performance content experimented with and rejected, it took a while for the performance content to hit its stride, but once it had I was able to put all of my technological knowledge to the challenge of applying It to the piece, a challenge that while not easily overcome, was immensely satisfying along the way.

Live!

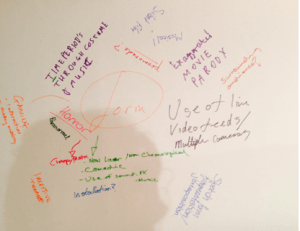

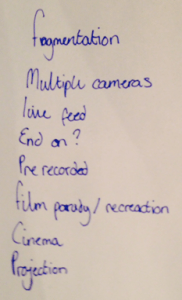

As we began to make considerable progress, a constructed performance was beginning to form, and I began to focus on the technological and visual components, one incredibly crucial motif began to develop in the practices in which we were engaging, the exploration and exposition of practicing live.

From both audio and visual standpoints, the devices that were more exciting, stimulating and rewarding, were those that were activated, manipulated and controlled in real time alongside the performance. It became a personal endeavor to rely on as little pre-recorded footage as possible, and more crucially as little formulated, visual set pieces instead of being compiled into a pre-edited video, were switched between, and became a much more organic experience.

We wanted the performance to not be a prepared presentation, but to be very much live; to be constructed, mixed and performed simultaneously, or at least implied to be, with as much of the organics and procedures exposed to the audience as possible.

However, as the performance began to come together, it became apparent that without significant practice, seamlessly controlling the media in its unassembled form proved too difficult, and pre-edits had to be made. Given the opportunity to perform the piece again , and have longer to practice, the complete real time compilation would have been much more effective.

We also began to experiment with expanding outside of the predetermined performance space, utilizing the live feed capabilities of the cameras to produce real time expansion.

The first experiment we conducted with this method was during the exploration phase of torturing. During group work, we set out to restage a scene from the Film Reservoir Dogs, in which one character tortures another. During the scene he torturer leaves the building, retrieves the jerry can from their car before returning to the victim, all the while being followed seamlessly by the camera. We restaged this by having our performer leave the stage via the wings, and similarly enter a backstage area to retrieve a prop, again followed by the camera. It was this act of expanding from the established space and into another all that genuinely excited us, and made us want to investigate it more.

Eventually, this devise was utilized during the Columbine and Hitler/Anne Frank sequences.

The Crows’ Nest.

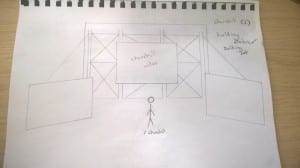

So when it was decided that the implementations of the technology were to be actively shown to the audience, we began to consider the possibilities of having said control mechanism, and those in control onstage at all times. Eventually the decision was made to facilitate the use of a scaffolding-like structure, with the technology and operators on top, above the performance space. The second onstage tech-box, that colloquially became known as the ‘Crows’ Nest’ gave the appearance of an overbearing controlling presence throughout the entire performance, an effect we were enforce, as it exposed to the audience our manipulation of the technology, and created the illusions of an omnipresence within the universe of the performance.

Vision Mixer and Wirecast.

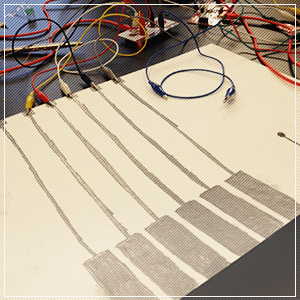

So if control was the key aspect t of our presence onstage, the mechanisms, which I used to control the various on stage assets, are ultimately important. To control the cameras which live feeds were displayed on the two side of stage screens, I had use of a vision mixer. This machine allowed me to allocate one of 5 visual inputs; (3 separate cameras, a blank feed, and colour bars) to each of the two screens; in short, it allowed me to control what went where. However, similarly to the live compositional element, a lack of practice made the full use of the technology impossible, and I was forced to keep its operation fairly simple to avoid error. Given more opportunity to practice I believe I could utilize the hardware closer to it’s full potential.

For the large rear screen, which displayed the prepared movie sequences, still images, and the live feed from the GoPro, I used an application on my laptop called Wirecast Studio. Designed for live streaming, Wirecast allowed me to seamlessly switch between assets and sources rather simply via the interface, so I was able to prepare the next scenes assets easily, before switching to the output of a projector screen.

Going Pro

About 5 weeks before the performance date an idea struck us for a possible addition to our inventory of visual technology; a GoPro. The tiny robust camera which has gained its prestige on video sharing websites among the likes of YouTube has gained its notoriety amongst extreme sports for example skiing, snow and skateboarding, skydiving, various mediums of racing and combat simulators like airsoft or paintball. Exactly why the famous brand of camera has become so widely used can be attributed to various features in which the GoPro line pioneers. It’s compact size and incredibly durable housing along with the ridiculous amount of mounting options allow the camera to give an audience the view of pretty much anything it can be attached to, but possibly it’s most crucial feature is its ultra wide angle lens, which has a much wider field of view than standard lenses, and simulates the peripheral vision of the human eye. When combined with a head or chest mount, this grants an audience relatively authentic point of view, resulting in heightened immersion. So for example within these sports, the audience can experience a close representation of these aforementioned sports from the point of view of those playing it, a view that would not be possible with conventional and/or larger cameras.

Churchill/Columbine/Hitler

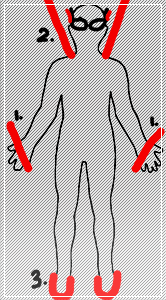

Returning to the GoPro’s compact size, we wanted to utilize the cameras ability to capture unconventional viewpoints, and video images of unique perspectives that would not be possible with conventional cameras due to both the logistic and indiscreet limitations of their size. The two methods we developed for experimenting this compact designed were during the columbine and Churchill sequences.

For the duration of the Churchill sequence we wanted to show footage and play audio of a record play turning idly to create ambience while the performers presented their monologues. Whilst this was simple aesthetic feature, designed more to compliment the scene than contribute to it, as record players can only be loosely connoted to the cultural icon, we surmised that simply playing prerecorded footage of said player would not only appear disjointed for the sequence, but also detract from it as a whole. However, in keeping with out our live motif, and with the Record player was clearly visible to the audience at the front of ‘the crows nest’ and was manipulated as equally in full view, the live footage offered simultaneous perspectives of a small but crucially live aspect of the scene, which upheld the exposition of our technological workings to the audience, but did not detract from the performers onstage. Furthermore, the GoPro’s minimalist profile allowed the presence of the camera to not be immediately noticeable, allowing the simultaneous footage of the player to peak the audience’s interest, and initially establish the GoPro’s presence.

Within columbine sequence, the performers aspired to rein act or represent the infamous library shootings. We felt that a conventional third-person view camera of the reenactment would be out of place with the rest of the show, creating an undesired cinematic experience rather than the perspective sharing performance in which were aspiring towards. It was during the formulation of this sequence in which the acquisition of the GoPro was decided upon, as we wanted to use an unconventional perspective during the sequence; that of the brothers who committed the shootings. So after acquiring the GoPro we attached it to rifle so during the representation the audiences is subjected to the point of view of the firearm, a very personal and visceral viewpoint. The viewpoint was also intended to replicate the common first person shooter genre of video games, a cultural that often negatively attributed to the shootings.

A Slight limitation presented by the workings of the GoPro’s wireless streaming mechanism was that the display of the camera’s footage was delayed by approximately 1.5 seconds. While a slight inconvenience, it produced an interesting and coincidental effect when the camera, which was still attached to the rifle, was pointed towards the audience, as they were confronted just over a second later by footage of their own reactions on the large screen.

With the Hitler and Anne Frank sequence, the GoPro’s Point-of-view style imagery was utilized in a more symbolic style. The Camera, mounted to a performer’s, head thus filming from their point of view, was walked through the set dressed backstage area of the auditorium. The footage was displayed on the large screen, simultaneously with a performer reciting a passage of Ann Frank’s Diary. The footage would show the performer’s arms when ever they interacted with the environment, but while originally the character was intended to be a symbolic Hitler somewhat comically searching for Anne frank, t became apparent to us that with the disembodied nature of the camera’s first person perspective viewpoint, the character become an allegorical personification of the oppressive political movement of Germany during the second world war. As the sequence took place after Columbine’s in the productions running order, so the ontological state of the back stage area having previously been established to the audience, the slow and deliberate approach of the performer towards the stage would be incredibly overbearing. Further more, the audience are once again confronted to their own image prior to being observed by the inhuman character.

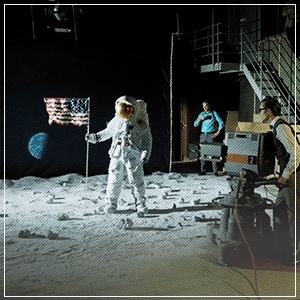

Moon Landing/Freddie Mercury

For the Moon landing and Freddie Mercury sequences I wanted to utilize as many still images as I possibly could to confront the audience with a plethora of images of the according topics. With Moon landing, the intention was to comment on the sheer volume of mediation the event has received in the decades since, and with the Freddie Mercury Sequence to shock the audiences with the uncomfortable reality of it’s underlying context; the awareness and effects of aids.

Big Bang/Wright Brothers/Suffragettes.

With these sequences, the performers were the prominent components, therefore I decided to keep and visual components as simple as possible, each containing a loop of simplistic or minimalistic video footage.

Trial and Error/Logistics

Possibly one of the most satisfying parts of creating this performance has been experimenting and problem solving in terms of the technology. Over the course of the process innumerous technological complications and set backs have arisen and overcoming them has been unendingly satisfying.

For example, on of the biggest challenges has been understanding and combatting the limitations of the vision mixer. During the earlier stages of formulating the production, the original intention was to control the distribution of all of the visual assets, i.e. both the live feeds from the camera, and the media controlled on the laptop, via the mixer, to all three of the screens an operation that proved to be technologically impossible. The limitations attributed to the mixer’s inability to process digital imager, i.e. the laptop’s HDMI or VGA outputs, being only able to control analogue video signal, which the cameras used. Furthermore the machine was designed to output to only one machine with the option preview monitor. After experimentation we were able to construct a system in which the mixer could control two screens simultaneously, but were forced to sacrifice the preview monitor and the ability to use visual transitions, meaning the live feeds could snap on and off, but not fade etc. The result of this was that the camera feeds were restricted to the two side screens, and the media controlled from the laptop to the rear. This posed the logistical issue of reorganizing the intended visual assets for each of the sequences to accommodate for this limitation. However upon reaching a finalized and operational system for all was incredibly satisfying.

Similarly the learning of the application Wirecast Studio for the organization and playback of the media assets proved an equally frustrating but rewarding experience, as the feeling of self-achievement when the two systems worked simultaneously was spine-chillingly exciting.

In reflection I believe that only a small percentage of avenues were explored technologically, with many devices not being used to their full potential, and with more time hands-on, or more intermediate training with some of the equipment more elaborate and polished devises could have been utilised. That being said, I am immensely proud of the work I have done for this performance, and of Changing Faces Itself.

Here you can find a playlist containing all of the assets created and used during the process.